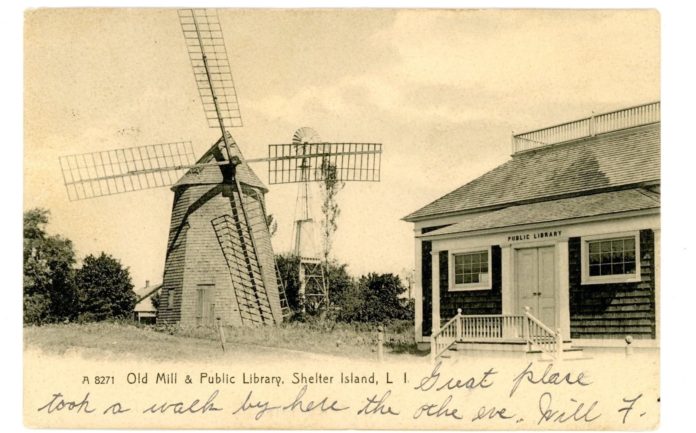

Before (or after) listening to “Life Between the Ferries, Episode 2” take this Shelter Island Windmill photo tour. It features images of the mill — now the iconic symbol of Sylvester Manor Educational Farm — from the Library of Congress. They were taken in 1978 as part of a National Park Service project to make a record of the historic structure.

Shelter Island Windmill photo tour

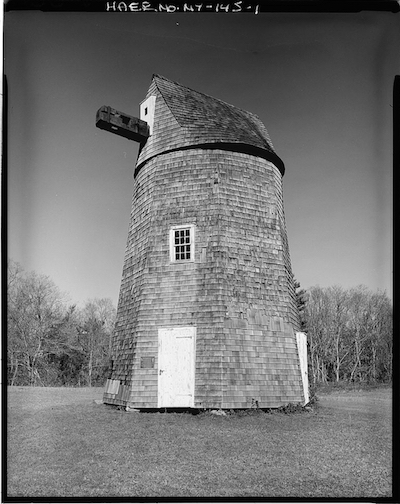

Windmill Exterior

Shown with the wind shaft in place, but without wings and cloth sails. The three-story octagonal structure sits on a rise in Sylvester Manor’s Windmill Field. It was moved there in 1926 from a former location in the town center thanks to Cornelia Horsford, a Sylvester descendant. A smock mill (the shape resembles a smock), it was built in Southold in 1810. Nathaniel Dominy V, a prominent East End millwright and clockmaker, designed and built the mill. In 1840, it was brought to Shelter Island, where it was operated for many years by miller Joseph Congdon. The entire top of the mill can be rotated so as to best catch the wind.

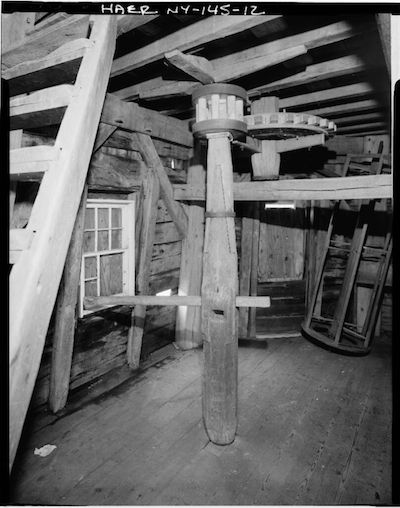

First Floor

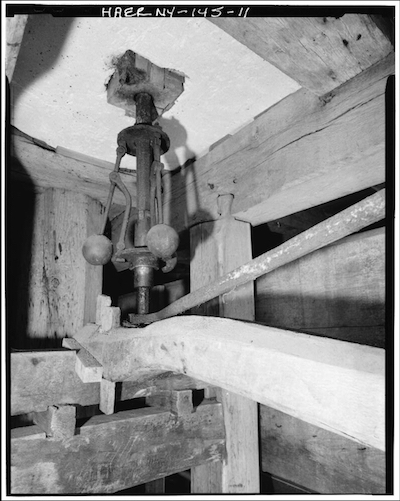

Massive timbers are found throughout the mill. Primarily oak, along with other hardwoods. The Shelter Island Mill is singular among surviving mills in that it is made almost entirely of wood, including ‘tree nails’ (aka trunnels) used in joinery. Some metal was used, but wood on wood gearing reduced the risk of sparks setting fire to the dust created when milling grain. (BTW — we’re told that the gears would’ve been greased with animal fat or beeswax.) The vertical pole with the horizontal rod is part of the winding mechanism to move the mill cap. By pushing the bar and turning the pole, the miller could engage the large wooden gear that would turn a large shaft to rotate the mill’s cap.

Heavy work

Customers would bring grain to the first floor and the miller would carry the heavy sacks up the steep ladder to begin the milling process. Note how the step treads are worn down. The Shelter Island Windmill, unlike others that Dominy built, did not employ a lifting mechanism to carry grain sacks up to the hoppers.

Second Floor

The large gear in the center of the second floor is called the great spur wheel. It’s turned by wind power transferred via the shaft that comes down through the ceiling. The spur wheel rests atop the mill’s massive center post. Two upright lantern pinion gears can be engaged against the spur, together or separately. Called stone nuts, these gears spin the two upper stones that are positioned over stationary bed stones. The pairs of stones are encased in boxes called tuns. Above them are grain hoppers.

Only the capstones, or running stones, move. They sit just above (but not in direct contact with) the bed stones. The faces of the stones are etched with grooves in a traditional pattern settled upon over hundreds of years of millstone design. Grain from the hopper is fed into the eye at the center of the running stone. As the grain is cut, the resulting product travels along the etched grooves to the stones’ outer edge. There, it falls through chutes and gravity carries it to the first floor to be sifted and bagged.

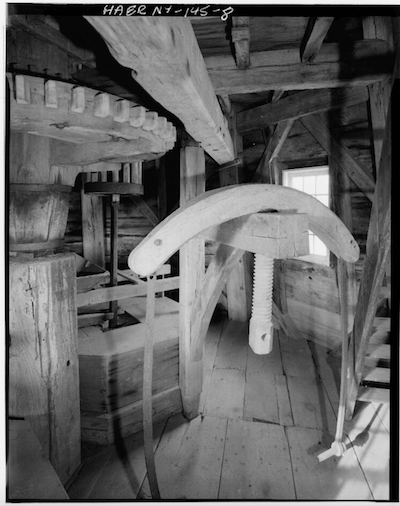

Stone crane

Also on the second floor is a stone crane. This essential piece of equipment allows the miller to lift the stones for sharpening. The Shelter Island Windmill crane is a rarity, as it was made almost entirely of wood. A yoke is attached to a bracket with a wooden screw (pictured in 1978, but missing today). Metal bands, called dogs, hang from the yoke. The bracket swivels so the pegs at the ends of the dogs can be fit into holes drilled into the sides of the stones. The miller lifts the stones by turning the screw and swings them away so their cutting faces can be sharpened by a specialist mason called a stone dresser.

Third Floor

At the uppermost level is the brake wheel. This enormous gear — 7 feet 8 inches in diameter — has 60 hand-bevelled wooden cogs. It’s mounted on the massive wind shaft, which passes through the opening in the cap to hold the sails. The brake wheel is the mill’s primary gear wheel. Power from the wind is transferred from it through a series of gears below. An essential element is the brake, that — along with other devices (see ‘governors’ below) — allows the miller to regulate the turning action.

The brake and wallower

A jointed lever enables the miller to set or release the brake, which wraps around the outer edge of the brake wheel. The brake wheel’s bevelled teeth engage the upright cylindrical trundles of the wallower, a type of lantern gear found — like other parts of the windmill — on a much smaller scale in clocks. And, as in clocks, the trundles show wear from rubbing against the cogs. The wallower turns all other gearing within the mill, including the great spur wheel. The small gear at floor level (bottom left) transfers power to a secondary off-drive for auxiliary machinery, like belts to rotate the bolters.

Centrifugal governors

Centrifugal governors, invented in the 17th century, also help regulate the speed of a mill. Three iron balls are attached to a collar that spins as the millstones go round. As the speed increases, the balls swing outward on their hinged legs. Pressure caused by the movement of the weighted balls is transmitted by levers to incrementally raise the spinning stones. This slightly increases the gap between the stones, allowing somewhat more grain to fall between. This added load slows the stones. Concave hollows are cut in the posts and beams to make room for the spinning balls.

Bolters

Back on the first floor, the ground material falls from the stones above through chutes into two enormous devices called bolters. The bolters, which would’ve been covered by fabric, resemble giant box kites. They’re 15 feet long and are built around a central spindle. Dowels radiating from the spindle attach to beater boards that make up the sides. The whole apparatus is set on a angle, titling downward from where the milled material enters. The spindles are turned via belts that attach to the off-drive on the second floor. As the bolter spins, flour is forced by the beaters through the fabric shell and then falls into the wooden trough below. Gravity causes heavier grains to collect at the lower end. The miller bags the various products, retaining a share to sell to the public.

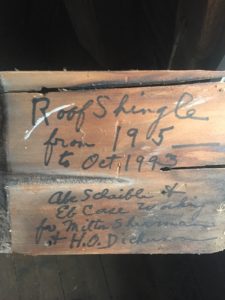

Shingle notes

Notes found on two old roof shingles describe work done on the windmill in the 1950s and 1990s. On the back of one shingle is the message “Roof Shingle from 195_ to October 1992” and lists as workers who installed the roof as “Abe Schaible and Eb Case working for Milton Sherman and H.O. Dickerson”. A second shingle describes the current roof as having been supplied in “October 1993 by E. Case Builders and Ken Martison” with the correct prediction that the roof “Should last until 2018+”.

How to contribute

If you’d like to contribute to refurbishing the mill, you can do so online at sylvestermanor.org. Be sure to select Windmill Restoration Project from the list of campaigns.

Credits

The Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) is a project of the National Park Service to preserve records of historic structures. John T. “Jet” Lowe took the photographs in 1978. Historians Robert Hefner and Kevin Murphy compiled an accompanying report that was filed in 1984. The three also teamed up to look at other East End windmills.

See the full 14-image slideshow on the Library of Congress website. You can also read the accompanying report, including details about the mill contained in letters from Nathaniel Dominy V.

Our notes on the images are gleaned largely from our conversation with Bennett Konesni, Sylvester Manor’s co-founder, and from information provided by Hefner and Murphy in their reports about Long Island windmills.

Podcast

And, if you haven’t already, check out our podcast, Life Between the Ferries.