The Town Board continues to mull a conceptual wastewater plan to cut nitrates in drinking water by piping liquid sewage from municipal buildings to a new treatment facility at Klenawicus Airfield.

[Editor’s note: On April 20 the Town Engineer identified a new location for the facility. The other details in this article remain relevant. Learn more about the new location by following this link.]

Before the holidays, Pio Lombardo and Gary Rubenstein of Lombardo Associates presented their proposal, funded by New York State and Suffolk County grants.

With board approval, the project for the Town Center would move to the design phase, also covered by the grants, which total nearly $72,000, Town Engineer Joe Finora said. Grant funding includes $30,000 from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and $41,925 from the county’s water quality improvement program.

The board next takes up the matter on Tuesday, January 11. Supervisor Gerry Siller says the meeting focus is for Town committees to weigh in. But the Zoom meeting is open to the public. Find the login details here.

And Finora anticipates many other opportunities for public input.

Read on to learn more. If you still have questions, send them to jfinora@shelterislandtown.us.

Major new infrastructure for public health crisis

The concept — complex and deserving of attention — contemplates the first new major infrastructure in the community in many years.

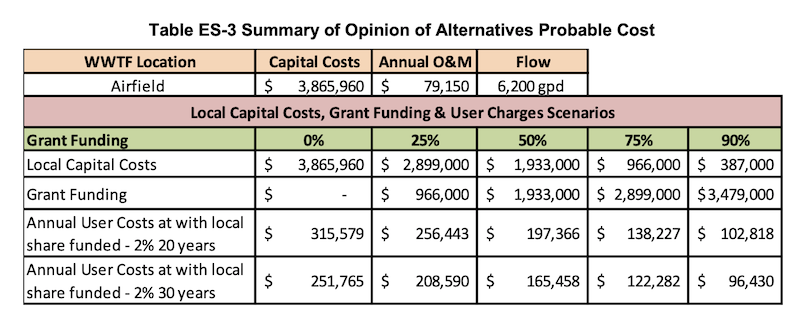

The estimated cost is $3.8 million (additional grants may offset some or most), with about $79,000 in annual operations and maintenance.

While the proposed solution for nitrates in the Town Center “represents a higher sticker cost” than some other options, Finora said, “the life of these systems is on a scale of decades.”

“We’re dealing with a public health crisis at the center of Town … in areas with the majority of year-round residents and the majority of younger children,” he said.

“We can take responsibility for the municipal buildings here and help reduce our impact in that known crisis area.”

[See the full report or executive summary (both on the Town website) or watch the Town’s YouTube channel presentation.]

This post combines details from Lombardo’s report with insights gleaned during the firm’s presentation, along with comments from those who attended the meetings to date.

A tight timeline

The state grant covers costs through the design phase under a tight planning timeline:

- Engineering Report Presentation to Town Board, December 14, 2021

- Town Review, December 2021 to January 2022

- Submission to NYSDEC for permitting, February to April

- Design of Recommended Alternative Grant Funding Application, March to July

On December 14, Lombardo walked the board through the conceptual plan.

The goal is to collect liquid sewage from eight municipal buildings in the Town Center because such facilities generally produce higher concentrations of nitrates. Their primary wastewater source is toilets, Lombardo said.

“There are no showers; there are no washing machines. It’s just bathrooms,” he said.

He expects nitrates in the collected wastewater to be 125 to 150 milligrams per liter (mg/l). Unlike the septic treatments in place, the proposed system would reduce nitrates to 3 mg/l.

That’s well below the 10 mg/l drinking water standard.

The Town controls five of the buildings: the Community Center, Town Hall complex, Town-owned residential rental building, Police Department HQ, and Justice Court.

Independent governing bodies operate the Center Firehouse, Shelter Island Public Library, and Shelter Island School. But they’re funded by the same taxpayer base and can readily combine for permitting purposes.

Sewer basics

Keep in mind that the basics of wastewater management are:

- Collection

- Treatment

- Disposal or reuse

Therefore, the engineers’ first step was to determine which collection system to use.

Lombardo recommended a septic tank effluent system. Tanks would remain on each of the eight properties to collect solids (pumped out periodically). Instead of liquid effluent flowing into nearby leaching fields, as it does now, it would flow into a new collection system.

The liquid would then proceed to a treatment plant, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Establishing design flow

The next step was to determine how much wastewater was involved.

Lombardo’s team followed standards set by the NYS Environmental Facilities Corporation (EFC) and the DEC, which regulates municipal wastewater systems.

Doing so ensures that their report meets requirements specific to public wastewater projects and retains eligibility for EFC funding and other grants.

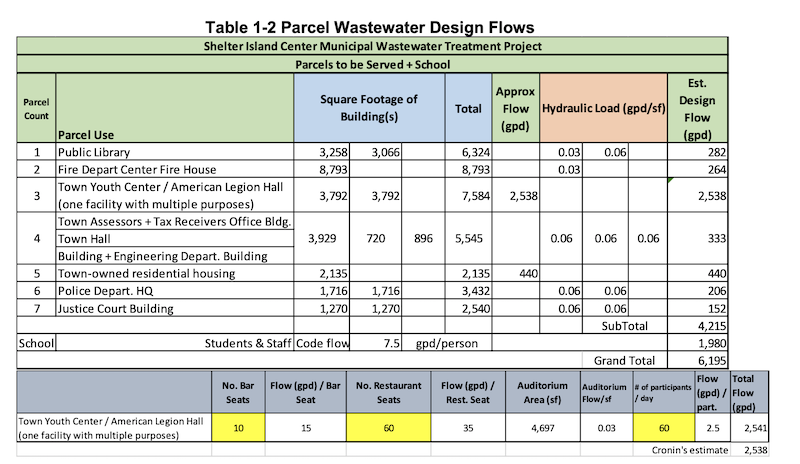

First, the firm analyzed each building’s potential wastewater flow. In DEC terminology, the flow estimates are “code flows.” For each facility, Lombardo presented them as gallons per day (gpd):

- Public Library, 282

- Center Firehouse, 264

- Community Center, 2,538

- Town Hall Complex, 333

- Town-owned residential housing, 440

- SIPD HQ, 206

- Justice Court. 152

- School, 1,980

Including the school, the total system capacity must be at least 6,195 gpd; without the school, 4,215 gpd.

The school had already begun to plan for septic upgrades, and Superintendent Brian Doelger and an architect working on the district’s plan were at the December 14 meeting.

While state officials are already reviewing the school’s plan, Doelger said the district would prefer to join the Town proposal.

He agrees with Siller that a combined project would be more cost-effective for Island taxpayers than separate upgrades.

“We are on board with anything feasible that saves the Shelter Island taxpayer as much money as possible,” Doelger said.

Why such high flow at Community Center?

Ianfolla questioned the high flow estimate for the Community Center, which houses town recreation programs upstairs and American Legion Mitchell Post #281 downstairs.

Because the Legion Hall operates a restaurant (albeit part-time), Lombardo said the engineers had to use the DEC allowance of 35 gpd of wastewater per seat.

“You have to design it on its potentiality?” Ianfolla asked.

“Exactly,” he replied. “Because at the end of the day, the system has to work under the most extreme conditions.”

Lombardo said average flow is typically 50 percent of the code flow allowance. “But if you design for the average, half the time, it’s not working.”

Hydro-geological features

The next step was to find a suitable location for a treatment facility by looking at various hydro-geological features.

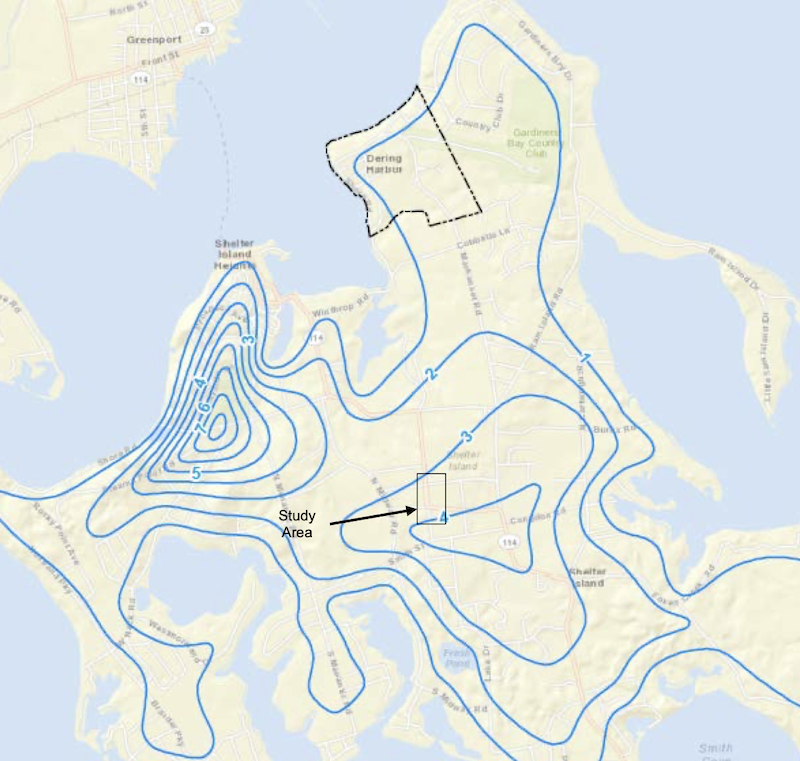

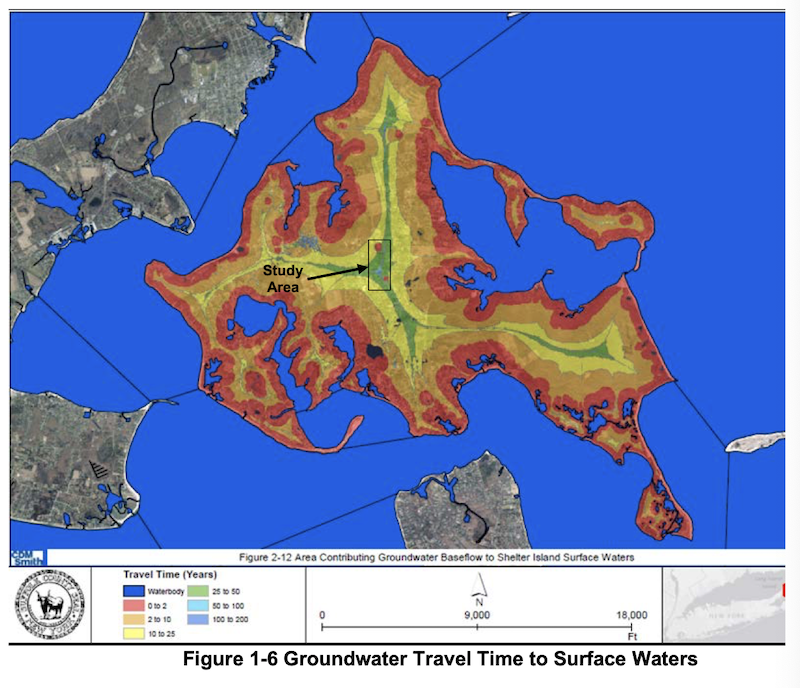

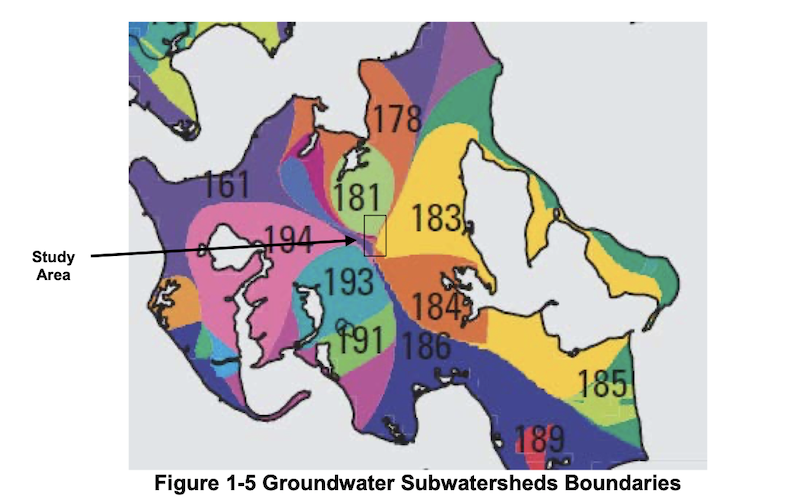

Lombardo displayed four maps of the Island to show:

- Elevation contours

- Groundwater travel time (in years) to surface water

- Sub-watershed boundaries

- Nitrate-nitrogen (Nitrate-N) levels

As you may know, groundwater is drinking water; surface water refers to the saltwater surrounding the Island, its freshwater ponds, and the wetlands in between.

On the elevation map, contour lines show the Town Center — roughly Route 114 from the Center Firehouse to the Shelter Island School — occupies one of the Island’s highest elevations.

“When you’re on the top of the watershed, ” Lombardo said, anything discharged “is going to be in the groundwater for a long time.”

Based on Suffolk County and the United States Geological Survey (USGS) data, the groundwater travel time map shows the Town Center is also one of a few Island locations where groundwater takes 50+ years to flow to surface waters.

On that map, a tiny area of blue is surrounded by broad bands of green (representing 25 to 50 years), yellow (10 to 25 years), orange (2 to 10 years), and red (0 to 2 years) until reaching the shoreline.

“So if you’re concerned about contaminating the groundwater, this is the worst spot to be,” he said.

Soils and sub-watersheds

Subsoils influence both the pace and direction of flow. The engineers relied on USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service surveys to predict soil types.

The surveys say Montauk-Haven-Riverhead Association soils primarily characterize Shelter Island. These tend to be deep, nearly level to strongly sloping, well-drained to moderately well-drained, having moderately coarse-textured and medium-textured soils on moraines, the USDA says.

Meg Larsen, a newcomer to the Town Board, works for her family’s company installing septic systems. In her experience, she said the airfield area has significant clay deposits.

Lombardo said engineers would study soil borings during the design phase to confirm what’s underground and plan accordingly.

Next, Lombardo showed a map with sub-watersheds numbered and depicted in blue, purple, pink, yellow, orange, and green. On it, the Town Center is at the vortex of numerous swirling colors, radiating like designs on a tie-dyed shirt.

These sub-watersheds, Lombardo said, aren’t static. “They change and move depending on rainfall patterns.”

Wastewater from septic systems in the Town Center could travel in various directions but moves predominantly into a sub-watershed marked #183, which flows into Coecles Harbor.

Lombardo said the proposed Klenawicus Airfield treatment facility is also within that sub-watershed. So, the wastewater will end up in the same area but be much cleaner after treatment.

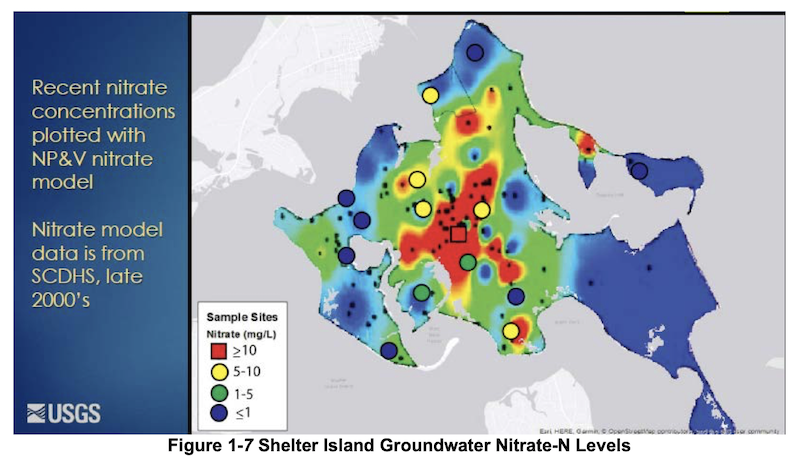

The fourth map is one familiar to Islanders. It shows data from a USGS mathematical model that indicates nitrate-nitrogen in groundwater in the Town Center is above 10 mg/l.

With the highest levels depicted as red blobs, the map shows the Town Center “is overloaded with nitrate-nitrogen,” Lombardo said.

Not only are most of the Town’s municipal structures clustered in the Town Center, but as Finora pointed out, many year-round residents live there, as well.

“The groundwater in the Center is really in violation of drinking water standards,” he said.

Needs analysis

The engineers also did a needs analysis.

First, they looked for septic system malfunctions where, as Lombardo put it, “the wastewater just doesn’t go away.” Examples are plumbing backups, flooded drain fields or breakouts, foul odors, and excessive pump out. They found none.

“You don’t have that issue here because you’ve got very forgiving sands,” he said.

Next, they judged how well the systems remove contaminants.

The Town Center systems “do not remove contaminants sufficiently,” Lombardo said — nitrogen particularly.

Most Island buildings use individual septic systems (except in the Heights, where the Shelter Island Heights Property Owners Corporation has a sewer system). And most do not provide thorough nitrogen removal.

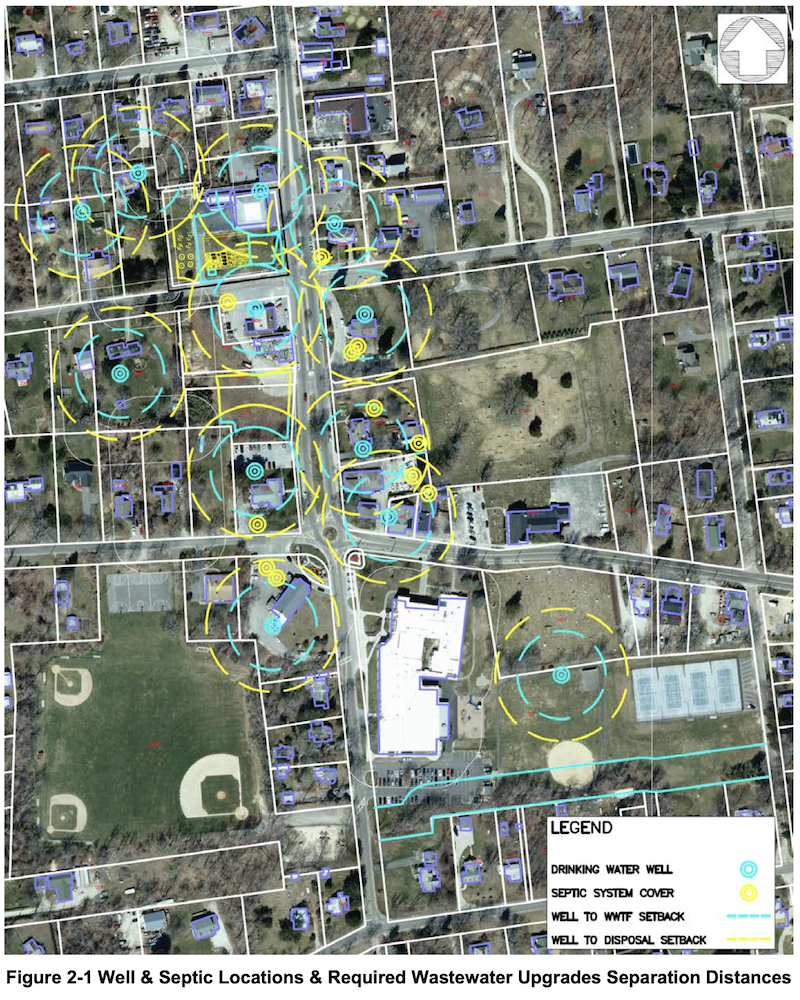

Lastly, the engineers checked for space constraints. When a septic system needs to be replaced (as it inevitably will), there must be room to upgrade within setbacks from wells and other septics.

Lombardo showed a satellite view of the Town Center overlaid with blue dots representing drinking water wells and yellow dots for septic tanks at the eight municipal buildings and immediate neighbors.

Surrounding the blue well dots were blue rings showing the 100-foot minimal distance from well to septic tank, and somewhat larger yellow rings showing the 150-foot distance from well to wastewater disposal systems.

“So the only places where a wastewater system could be installed is where there’s no circles,” he said.

Possible Center locations

Just two areas in the Town Center have space enough to serve all eight buildings. One is the Center Firehouse, under the back and side lawns.

However, the Fire District would have to agree to host the treatment plant, which may complicate permitting. And the layout would impede certain traditional gatherings there.

The other location comprises two side-by-side, privately-owned, undeveloped parcels on North Ferry Road between the library and the Dandy Liquor store building. Lombardo said the two lots must be combined to provide sufficient space.

What’s more, he said, “the Town would have to acquire them in some manner.”

School playfields are too close to a well site, he said, and using them would mean giving up valuable recreational space.

Ianfolla asked whether the Town could combine its three contiguous properties — Town Hall, the residential rental, and SIPD HQ — and serve them by a well at one end and an upgraded septic system at the other.

“That’s doable,” Lombardo said. However, it wouldn’t solve the problem created by all eight buildings. And, while the effluent would be cleaner, it would still be at the top of a watershed heavily loaded with nitrates.

Not just about nitrates

The Lombardo team did not test for PFOA (used in carpeting, upholstery, apparel, floor wax, textiles, fire fighting foam, sealants, and more) and PFOS (used in oil, stain, and water repellants for carpet, fabric/upholstery, apparel, leather, metal/glass, bags, food containers and wrap, among others).

Read about these compounds on the DEC website. Throughout the region, there is a concern that the groundwater may contain these ubiquitous hazards at levels above New York’s drinking water standards.

Lombardo said the EPA announced it would soon be issuing drinking water standards for PFOA/PFOS.

Thus, the selected treatment facility site should also have room to treat these and pharmaceuticals, along with other emerging contaminants, he said.

Off-site locations and the speed of flow

Lombardo’s team looked at Town-owned areas outside the Center, avoiding those co-owned with other entities to streamline approval processes.

They found four locations and gave evaluations for each:

- Kelanwicus Airfield, deemed highly desirable because of the short time to surface water, few downgradient homes, and “lots of open space”

- 99 North Ferry Road (Sachem’s Woods), deemed undesirable as discharge would remain in the groundwater with decades of travel time

- Goat Hill Golf Course, undesirable because it’s a public water supply recharge area (for both the Heights and West Neck water districts)

- North Menantic & Bowditch Roads areas, undesirable because it’s a former landfill

Ianfolla asked Lombardo to clarify why faster speed to surface water is desirable. “We want this going into the bay?” she asked.

“It’s going into the bay,” he replied. “That’s where all of it goes.”

“We want that to happen quickly?” Ianfolla asked. “Not with a lot of time underground?”

“All of the treatment that occurs, occurs in what we call the drain field,” he said. (That’s where liquids from a septic system percolate through surrounding soils.)

“There’s some that occurs in what we call the unsaturated zone,” he said. (That’s the area just above the water table.)

“But once you get into groundwater, there’s no further treatment,” he said.

Ianfolla noted that Coecles Harbor “doesn’t have a good flush,” likely due to its narrow opening onto Gardiner’s Bay at Reel Point.

Lombardo said he looked at that. But contaminants from the Center are predominantly making their way there now, and discharge from the treatment plant would be significantly cleaner.

Faster is better

“Any contamination that does get in,” he said, “we don’t want it staying the groundwater because that’s your water supply.”

For the siting of a wastewater treatment facility, Lombardo said, from an “environmental perspective, it’s better to be closer to the bay.”

The proposed facility won’t add pollutants to the bay; instead, it would reduce contaminants “probably well over 90 percent.”

“That airfield location just means it’s going to get to the bay faster,” Lombardo said.

Do we have it backward?

Given the importance of speed to surface water, Deputy Supervisor Amber Brach-Williams asked whether the Town had it backward to prioritize septic upgrade rebates in the Town Center rather than near-shore regions.

Along with New York State and Suffolk County, the Town provides rebates to homeowners who upgrade aging residential septic systems with Innovative /Advanced (I/A) systems, which reduce nitrate in sewage before discharging it.

Town Code requires I/A systems for new construction and other situations.

“For our I/A grants, we’ve been focused on the center of Town because of the high nitrates for people and less so for the periphery,” Brach-Williams said.

Councilman Jim Colligan said areas on the Island’s periphery don’t have nitrate problems but rather have saltwater intrusion problems.

Lombardo said the advantage of moving the municipal discharge to a treatment site at the airfield “is predominantly to get it in a location where the travel time and impact on the aquifers diminish.”

“So if you have the ability to move the effluent to a location where it’s not going to negatively impact or potentially negatively impact your aquifer, we would urge you to do that,” he said.

Moving the liquids

So how would the liquids get to the proposed treatment facility?

Making use of the Town Center’s topography, liquid from each building’s septic tank would flow through a set of 4-inch collection pipes via gravity to a low spot on Bateman Road at the library.

A pump station would then force the liquid through a 2- or 3-inch pressure pipeline to the treatment site.

The consultants considered several routes for the pressure line but settled on one that:

- heads north on Route 114 to the IGA

- turns east onto Manwaring Road past Sylvester Manor

- jogs south onto St. Mary’s Road

- turns east onto Burns Road, to Klenawicus Airfield

The Town owns the proposed Klenawicus Airfield site, having purchased 17 acres in 2011 to support aquifer health (Suffolk County owns the neighboring 17 acres). Towns are permitted to use Community Preservation Fund (CPF) properties and money for aquifer protection.

But Gordon Gooding, who chairs the Town’s CPF Advisory Board, has asked for documentation confirming the proposed treatment facility is an acceptable use for this space.

Treating the effluent

To wrap your mind around treatment solutions, it helps to understand a little bit of the science involved. Here’s how the EPA explains it:

- Untreated domestic wastewater contains ammonia

- Nitrification is a biological process that converts ammonia to nitrite, and nitrite to nitrate

- Denitrification is another biological process that reduces the nitrate to harmless nitrogen gas

In the case of the proposed treatment facility, a series of interconnected modules (made up of pipes, tanks, pumps, and values) would hold and pre-treat the collected fluids. Initial pre-treatments would use readily available biological processes to spur the requisite chemical conversions.

Next, the system would disperse pre-treated effluent to pressurized shallow drain fields lined with Nitrex. That’s a patented material impregnated with slow-release carbon derived from wood that promotes biochemical reactions for groundwater denitrification.

As the treated wastewater percolates through the Nitrex medium, bacteria (with the aid of all that carbon) use nitrate rather than oxygen for energy, releasing harmless, colorless, odorless nitrogen gas.

Thanks to the Nitrex medium, Lombardo said the resulting fluid typically ends up with a nitrate level of less than 3 mg/l.

Among the advantages of the system: it employs a simple, stable process that uses little energy; requires no chemical storage or ongoing chemical costs; and creates negligible amounts of sludge, he said.

Cons associated with the system include a larger footprint and higher installation costs. Also, the Nitrex medium eventually is consumed and must be replaced, but not for about 40 years, Lombardo said.

To give a sense of what the site would look like, he showed a photograph of a Hampton Bays Nitrex facility, about twice as large as what would be needed here

“This type of system is very low-energy; it’s really just using pumps to move water around,” Lombardo said.

What’s with the trademark?

Throughout the report and presentation, the word Nitrex appears with a trademark symbol — Nitrex™. The product, invented at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, is protected by Canadian and U.S. trademarks.

Some in attendance questioned whether Lombardo derives a personal benefit from promoting the brand. His firm is advocating that Shelter Island use the Nitrex-brand filter because of its capacity to reduce nitrates. But, Lombardo said, he’s “agnostic on the solution” the Town chooses.

Beyond engineering fees of $79,634*, his company stands to make no “extra” money should the Town decide to use Nitrex or any other materials in the recommended design.

After all, the components will be purchased from and installed by vendors selected through standard bidding processes, he noted.

*The scope of work, Finora said, includes four tasks: 1) study, assess, and report feasibility $26,514 2) engineering estimates $1,189 3) design wastewater plan $49,706 4) document preparation $2,225 — with most funding from grants.

Estimated costs

The estimated capital cost, including construction, engineering, administrative and legal expenses, is $3.8 million. Lombardo estimated the annual operations and maintenance budget at $79,150 per year.

Lombardo said he conservatively estimated operator costs. The system is mainly automated and low-maintenance, requiring an operator to spend one day per week. Less operator time may be required once the system is up and running.

In the proposal, he laid out five potential funding schemes, ranging from the Town providing the entire capital outlay with no grants to the Town footing just 10 percent of the capital outlay.

He provided cost estimates for each scheme to bond the project for 20 years or 30 years.

“In my opinion, you the Town would be in a very advantageous position to get grants because obviously you’re a municipality and you’re dealing with water quality. “

He said that drinking water problems “go right to the top for grants and infrastructure funding.”

Because the Town already has a grant for the study and design phases, the project could be “shovel ready pretty quick.”

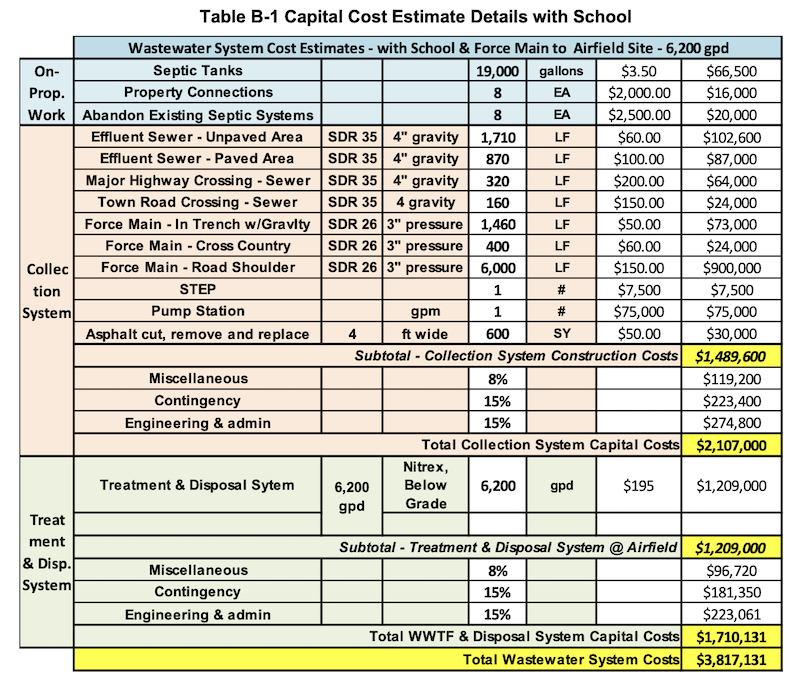

In another slide, he showed a breakdown of cost estimates:

- $2,107,000 for the collection system, including septic tanks for the eight properties, 3,060 linear feet of 4-inch gravity drain, 7,860 linear feet of 3-inch pressure pipeline, STEP, pump station, and 600 square yards of asphalt cut, removed, and replaced along the collection route

- $1,710,131 for the treatment and disposal system at 6,200 gallons per day

Both estimates include 8 percent for miscellaneous items; and 15 percent for contingency, engineering, and administration.

“We are very comfortable with these numbers,” he said. “If anything, they’re on the high side, so don’t be surprised if … the total price could come in under $3 million.”

In closing his presentation, Lombardo said the idea of constructing a system at the Center Firehouse is doable from a technical standpoint and less costly, likely under $2 million.

But Finora cautioned the board: “If we look at alternatives, we’re cutting ourselves short both from a technology standpoint and also from a long-term perspective, and that’s really the emphasis that we tried to make in the scope of this project.”

Operator qualifications?

Larsen asked Lombardo what qualifications a system operator would need. He said the ideal candidate has the chemical, mathematical, mechanical, and electrical aptitude to meet specific state licensing criteria.

There are system operators already working on systems on the South Fork, and his firm can provide training.

“It’s pretty simple,” Lombardo said, “We’re only talking about pumps, floats, and switches.”

Other safeguards?

She also asked what safeguards were in place to ensure the system would operate effectively if underutilized.

“So I know you’re designing for 6,000 gallons per day, but you’re probably going to get 2,000 if we’re being real,” she said.

Lombardo said the system uses modules and can shut off sections when demand is low.

He said other technologies don’t do well with varying flow rates, enthusing with Larsen about fixed-film versus activated sludge systems and the vagaries of Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) in wastewater systems.

This shop talk likely went right over the heads of many on the Zoom call but demonstrated the value of having a septic expert on the Town Board at this particular time.

Why not deliver clean water?

Michael Shatken, an architect advising the Town’s Community Housing Board, asked whether a better option would be to bring clean drinking water to the Town Center.

Finora said, for “this study, we’re not really tasked with establishing public water infrastructure.”

But, that should be “part of the discussion for longer-term holistic water solutions for the Island.”

While this particular project is limited to wastewater, Lombardo said the Town could do both: “You could have a wastewater system that’s centered in the in the center of town and a water supply system that serves those buildings as well.”

Siller said it was his understanding that the airfield site offered greater flexibility, mainly if the Town had to enhance the operation to treat other pollutants.

Lombardo agreed, saying the Center Firehouse site had “virtually no elbow room.” He also noted that his team looked at “a whole range of technologies.” (They’re outlined on pages 28 to 49 in the report.)

Ianfolla said a cost comparison of these options would be helpful.

What about water recharge?

Larsen asked whether Lombardo’s team considered the loss of recharge by pumping wastewater away from the Center.

Lombardo estimated the system would process about one million gallons of effluent per year, and given “the volumetric flow that moves through the aquifer, that’s a very small number.”

Relocating that amount to the airfield would have little effect on recharge in the Center.

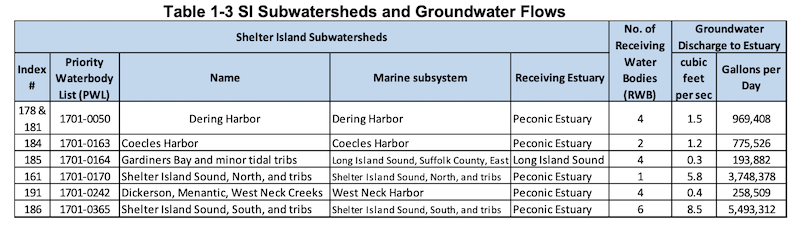

He shared a chart that shows enormous quantities of groundwater estimated to be moving through subwatersheds every day.

Do we need a water czar?

Patrick Clifford, president of the Hay Beach Property Owners Association, said he favors the project as proposed.

But, he’s concerned that several other private development proposals may be in the works.

Should the Town engage the services of a “water czar” to map other potentially sensitive areas, he asked.

For this particular project, Lombardo said, “the flows that we’re looking are here are pretty small.”

Development projects are required to undergo an environmental review process that he said can require “de minimus” impacts on the aquifer.

Recently in Hampton Bays, his company completed a project with zero nitrogen impact. “There are ways to engineer these projects so that they’re environmentally benign.”

Why not use I/A systems instead?

Ianfolla asked whether the Town could swap its aging systems for I/A systems. Lombardo said I/A systems couldn’t deliver the very low nitrate output of the proposed plan, 3 mg/l.

He said that systems approved for residential use don’t reduce nitrate levels in the outflow to 10 mg/l. And, once a system takes in more than 1,000 gallons per day, it must comply with code that requires getting total nitrogen to below 10 mg/l.

“The technologies you’re really referring to are residential technologies,” he said. “Some of them work fine. But whether they’re good enough is another question. In my professional opinion, in certain areas, they’re not good enough.”

“And, they’re certainly not equipped to handle the high nitrogen concentrations that you see in non-residential applications,” Rubenstein added.

“What we’re proposing here, the technology is rock-solid,” Lombardo said. “Gold standard, if you will.”

Possible expansion?

Tim Purtell, chairman of the Town Green Options Committee, asked how other users could join the proposed system.

Additional contributors could connect to the gravity drains and pump station near the library, depending on their location. Or, the Town could add new collection drains and pump stations, if necessary.

Expanding the treatment system would be a matter of adding modules, he said.

“That’s the nice thing about the airfield; we’ve got a lot of elbow room.”

Peter Grand, a member of the Water Advisory Committee, asked what the cost savings might be for a new user to join versus installing an individual I/A system.

Lombardo said he couldn’t provide estimates without knowing the specifics of the properties. But, since the major infrastructure was in place, costs to onboard new contributors would include any piping to make connections and, possibly, pumps if gravity flow was not possible.

Multiple additional users or high-volume contributors may require additional treatment modules, he said.

Shatken commended the project for advancing Shelter Island’s capacity to adhere to smart growth principles that call for building “where infrastructure exists.”

“In this case, what we’re doing is adding an infrastructure in anticipation of where growth should take place,” he said.

No expansion now

Despite speculation about possible expansion, the Town Engineer cautioned the current proposal is strictly for the eight municipal buildings.

“It’s not lost on us that laying the pipe down 114 and through some neighborhoods would raise some eyebrows either in a negative way or a positive way about the potential to [expand] the system,” Finora said.

“One major advantage of this system is that we’re essentially one customer,” he said. “It really aligns with the overall goals of the project for the municipality itself to help reduce its impact.”

“To not mix politics with engineering, the idea of future users is something that the board and the Town will have to make in the future if they think it’s right for them,” he said.

The option will be there, “but we certainly don’t want to address that issue at this time. It’s outside of the scope of this project.”

More discussions planned

In concluding the December 14 presentation, Finora said it was the first of many discussions.

However, a decision is time-sensitive for the school, where the septic system is seriously failing, and a separate plan is in the works to address it.

“We’re kind of pumping the brakes a little bit here,” said the school’s architect.

The school has a proposal before the State Education Department and is on track to present soon to the Suffolk County Department of Health Services.

While it can quickly amend its state approval, it would prefer to present just one proposal to the county.

Regarding the timeline, Lombardo said the Town proposal could be under construction by early 2023.

Want to learn more? Join the Town Board Zoom meeting on Tuesday, January 11 at 1 PM; follow this link for login details.